These days, many people enter medicine as a second career. I am no different. I was an undergraduate business major and worked in the corporate world of internet marketing for 6 years prior to medical school. Perhaps a science major would have been more practical when I was spending 7 hours struggling to understand some fundamentals of molecular biology; however, my business background did occasionally give me a leg up. Going back to school at 30-something, surrounded by recent college grads, I realized a few lessons I picked up along the way weren’t necessarily obvious to others.

1. Everyone has a job, and they all matter

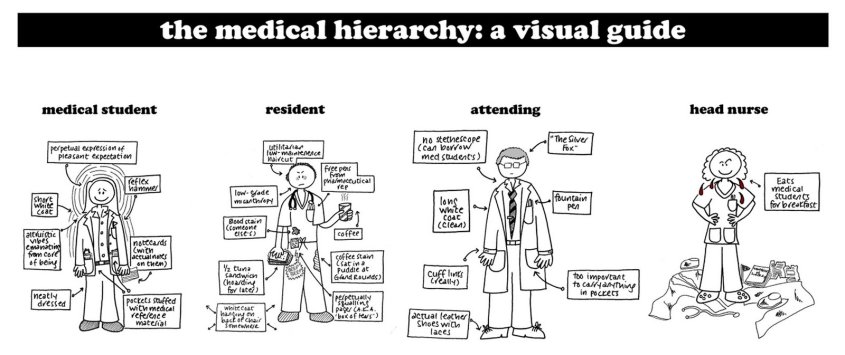

Despite modern movements away from it, medicine is an extremely hierarchical world. Medical students pine for that long white coat. Doctors bark orders at nurses without introducing themselves or asking nicely. Phlebotomists, lab techs, housekeepers and others largely go unnoticed.

One beautiful reality of capitalism is that jobs don’t exist unless they are vital… IMPORTANT. In medicine, we need janitors, doctors, accountants, secretaries. Everyone with a title has responsibilities and is therefore necessary for the organization to function. Companies with excess overhead from superfluous staff don’t stay in business very long (VA Hospitals aside). So when the surgical consultant steals a computer terminal from the ED Tech so she can finish her note, this disrupts work flow, and sends a message that somehow the doctor’s work is more important than the ED Tech’s. It’s just not true. Be mindful that everyone on the team has a job to do and people will want to be on your team.

2. “For-profit = evil” is not always the case

Yes, pharmaceutical companies are responsible for their reputations as greedy, evil, for-profit companies. Just ask Martin Shkreli. And while it would be great to provide free medications to any and all who truly have need, research and development (R&D) of new medications is risky and costs money. A lot of money.

On average, a new drug takes anywhere from 11-14 years to make it to market, and that’s IF the drug makes it that far. Of any new drug developed in a lab, there is an 8% chance that drug will actually make it to market, meaning it’s prescribed by doctors for actual patients.§ The money spent on R&D for 92% of unsuccessful drugs is a true cost, and those bills still need to be paid. Smart R&D focuses on modular development, so that one lesson learned developing a drug that failed can be applied to new research that will hopefully help a different drug get to market.

Yes there is excess and greed. Yes Big Pharma develops drugs based on profitability, not strictly based on need. People with “orphaned diseases” have to create non-profits and raise funds for R&D since the pharmaceutical companies won’t do it. It’s not ideal. Attracting the brightest minds to develop major pharmaceutical innovation requires paying people well, and I’ve yet to hear anyone tout how well-paid they are at their non-profit organization. In the end, it’s not as simple as saying “just lower the prices or make it free.”

3. Product perception is reality

Marketing is everything. You can have the best product in the world, but if no one knows it exists, or if consumers don’t understand what it can do for them, they won’t buy it. Similarly, you can get all the science right in medicine, but if results, diagnoses and plans aren’t communicated, getting it right doesn’t matter.

If anything this is even more applicable in medicine than business. While people have some innate understanding of what makes a good vacuum cleaner, they probably need more help understanding their liver failure and what treatment they need. I never assume patients understand their disease. Taking 5 minutes to explain the relation between the liver and ascites goes a long, long way.

4. Dress & Look the Part

Being a medical professional requires knowledge, honesty and altruism. Most people get that part right. But professionalism in medicine also means being on time, dressing professionally, and remembering that people are always watching. So for the EMT: put down the cigarette, tuck in your shirt and wear your gloves when needed. For the medical student: be the first one arriving to rounds, wash your white coat (not just once a semester either), lose the stubble and open toed shoes and ditch the piercings for the day. Doctors: wash your hands, put down your iPhone and give patients your undivided attention. All the knowledge in the world can be quickly overshadowed by a distracting or detracting exterior.

5. Listen to Customer Feedback

This is not “The customer is always right.” Medicine is different. Just because a patient thinks he needs antibiotics for his cold doesn’t mean he should get them. But your customers do know their bodies best and how they are feeling at the time. If you are handing a patient discharge paperwork and they “still don’t feel right,” stop and listen. In this case, the customer feedback is critical, and the price to pay may be high – both for the patient and for your wallet. Any seasoned Paramedic will tell you, “When the patient says they are going to die, I believe them.” We’ve all been there. And if you haven’t yet, it’s just a matter of time.

So that’s it, 5 small things. What lessons have you borrowed from an earlier career and applied to medicine?

~Steph

Stephanie Krebs and Amir Louka are two

Stephanie Krebs and Amir Louka are two