We all learned it in EMT-B class. The Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (CPSS) is the core assessment tool for EMS providers to evaluate possible stroke patients in the field. But, have you ever wondered where it came from? Why does it have 3 parts? Why test speech and not eyesight? What part of the brain is really injured? Let’s take a deeper dive.

What is the CPSS?

For a quick review, the CPSS is comprised of three individual tests, each of which get interpreted as either normal or abnormal by the EMS provider. The tests as well as interpretation are summarized in the table below.

Components of the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale |

||||

Adopted from Kothari, et al, 1996 |

Test |

Normal |

Abnormal |

|

1 |

Facial Droop

|

Patient smiles or shows teeth | Both side of face move equally | One side of the face does not move as well as the other (or not at all) |

2 |

Arm Drift

|

Patient extends arms out, closes eyes, and holds in place x 10 seconds | Both arms move the same, or both arms stay in position | One arm does not move or drifts downward compared to the other |

3 |

Speech

|

Patient repeats “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks” | Patient repeats back correct words with no slurring of words | Patient can’t speak, says the wrong words, or slurs words |

The CPSS is positive if any one of the three tests is deemed abnormal. In studies comparing Physicians vs EMS providers when performing the CPSS, when performed by an EMS provider, if the patient scored positive for one component, the sensitivity was 59%, meaning just over half of the patients who indeed had a stroke were identified by the EMS provider as having a stroke. The specificity was 89%, meaning that 89% of people who had a positive CPSS (1/3 components) indeed had a stroke. In other words, they caught just over half of the true strokes, but they also obtained a positive CPSS on some patients that didn’t have a stroke. The best example is a patient who is intoxicated. They likely have slurred speech, and therefore a positive CPSS, but aren’t actually having a stroke. Most tests in medicine are like this, you miss some, and you catch some that don’t really have the disease. We call these false negatives and false positives. Oh, and did I mentioned that EMT-Bs scored just as reliably as the Paramedics in the study?

The CPSS intentionally misses some strokes

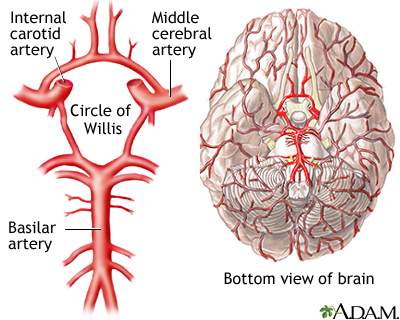

To understand what the CPSS is looking for, it’s important to know a bit about the history of how it was created and why. The CPSS was developed at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center in 1997. tPA had just been approved by the FDA in June 1996. The CPSS is derived from the NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS). You can read more about it here, but simply put, it’s a 15 part assessment where the patient gets scored according to their symptoms. The NIHSS was developed to identify neurological deficits that correspond to specific geographic tissue damage in the brain. MDCalc offers a great online calculator for helping determine a patient’s NIH Stroke Scale score. The NIHSS was condensed down, with some categories eliminated and some combined, to make the CPSS simple and easy to use, but also to help identify those patients who would be potential candidates for tPA. Not all strokes are created equal, and not all strokes are elligible for tPA, even if identified within the 4.5 hour time window. Strokes of the anterior cerebral artery and middle cerebral artery are better tPA candidates that other types of stroke. The CPSS focuses on identifying those strokes, but not posterior strokes for example.

The future of the CPSS and prehospital stroke identification

As I mentioned, the CPSS is not designed to detect things like posterior circulation strokes that affect the cerebellum, the balance center of the brain. Historically, efforts focused on early identification of tPA candidates. As new surgical and pharmacological advancements develop for other types of stroke, there’s a greater emphasis on early identification of all strokes. As such, there’s a lot of research going on right now studying new or modified prehospital stroke assessment tools. One front-runner is the B-FAST, which adds one more test to the CPSS to test for balance, and potentially identify posterior circulation strokes. The posterior circulation (basilar artery in the diagram above) supplies blood flow to the cerebellum, the balance center of the brain.

B – Balance, tested by having the patient walk

F – Face, same as CPSS

A – Arms, same as CPSS

S – Speech, same as CPSS

T – Time, to remind us that time is brain

If you want to impress with your turnover on your next stroke patient, be sure to test for balance disturbances by (carefully) ambulating your patient. If the patient stumbles or can’t walk without assistance, that’s a pertinent positive. In the original Cincinnati study by Kothari, the CPSS missed 13 patients with stroke, but 10 of those were posterior circulation strokes, notoriously difficult to diagnose clinically, and often missed by even the best Emergency Medicine physicians.

As always, feel free to share any tips you have on helping assess for stroke in the field.

~Steph

Attended a great “Advanced Stroke Life Support” class last Saturday at EVMS where the MEND exam is used. It was great to learn a new assessment tool and more about Strokes. The ASLS class was excellent and had some great information.

LikeLike