Originally posted on JPFreek.com

I always prefer the window seat. Mostly because I will hold my urine to the edge of kidney failure rather than try to cram my 6’5″ frame into an airplane toilet, and having to get up repeatedly to let my weaker-willed neighbors past makes my eye twitch. But there’s more to it than bladder control. I control the shade, and at my leisure I can peer out and down, unobstructed, over the great expanse below.

Just a few weeks ago, I found myself in that prized position, looking down on the vast Senoran Desert, on my way to Phoenix, Arizona. From twenty-thousand feet, it’s a wasteland. Seemingly random outcrops of red stone rise and fall away, separated by endless miles of nothing at all, except every few minutes we’d drift over one of those mega-farms with the funny patchwork of circular fields. With nothing else to do but think of the bone-crushing pain being inflicted by the seat in front of me, I found myself wondering, “Just how could those first settlers have made it all the way out here in their Conestogas?” Gold or not, it looked impassable.

Just a few weeks ago, I found myself in that prized position, looking down on the vast Senoran Desert, on my way to Phoenix, Arizona. From twenty-thousand feet, it’s a wasteland. Seemingly random outcrops of red stone rise and fall away, separated by endless miles of nothing at all, except every few minutes we’d drift over one of those mega-farms with the funny patchwork of circular fields. With nothing else to do but think of the bone-crushing pain being inflicted by the seat in front of me, I found myself wondering, “Just how could those first settlers have made it all the way out here in their Conestogas?” Gold or not, it looked impassable.

Soon after, we landed in Phoenix, a quilt of strip malls sewn together with massive highways. I was there for a conference, but arrived a day early to explore with my wife. We settled into our hotel and quickly planned a trip to Sedona, just a few hours north, and set off early the next morning with our GPS aimed for Barlow Adventures.

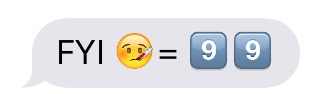

We arrived around ten, and our hearts sunk to find half-day rentals start at 8 AM or 1 PM. They were kind enough to squeeze us in anyway, and with just a glance at my insurance card handed over the keys to Jenny. Oh Jenny. A red four-door Rubicon with the hips of a belly dancer and treads of an M1 Abrams. To my wife’s mixed dismay and delight, I fell immediately in love.

The folks at Barlow gave us a quick, but thorough, tutorial of the best trails to suit our style – an easy climb to get acquainted, culminating in stunning views, followed by a technical crawl down into a valley full of history. With that, we put the top down, turned the radio up and got rolling.

Immediately, with a blue sky above us and red rocks all around, we felt we could conquer the world, just my wife, Jenny and I. Within a mile or two, we made it to the first trailhead and checked our notes. “When you pass the gate, put her in 4-HI and reset the odometer.” Done and done.

Schnebly Hills Trail is a winding, bumpy fire road up the side of what I can only assume was Schnebly Hill. Jenny plowed over everything in her path. The only thing limiting our progress was that we kept stopping to take photos because the scenery just kept getting better. Massive, imposing rock formations surrounded us with hardly another human in sight. Cacti, iron woods and the hot sun above us – it was the setting of every spaghetti western. At first, I tentatively wove my way along, afraid to test the limits of the $25 tire and glass coverage we’d added. But my lack of experience with off-road driving and the sharpest, most punishing rocks proved no match for Jenny’s sheer brawn. We made it to the top, where we went on foot to explore the “Merry-go-round,” a rocky outcrop boasting a jaw-dropping panorama of the entire valley. We sat down for a few minutes to soak in the sun and bask in the diem we were thoroughly carpé-ing.

If the way up was a learning experience, the way down was an educatio n in fun. A downhill slalom, probably at higher speeds than Barlow would have liked, with a Pearl Jam soundtrack provided by Jenny’s Sirius XM radio, Schnebly Hill melted away. At the bottom, once again on pavement, we consulted the maps provided to us to navigate our way to the next trail.

n in fun. A downhill slalom, probably at higher speeds than Barlow would have liked, with a Pearl Jam soundtrack provided by Jenny’s Sirius XM radio, Schnebly Hill melted away. At the bottom, once again on pavement, we consulted the maps provided to us to navigate our way to the next trail.

Soldier’s Pass was an entirely different beast altogether. This time our notes said, “4Lo, nice and slow.” I dropped Jenny into low gear and flipped the sway bar disconnect switch, allowing the axles to move more freely. Free is good. Let’s go.

The first thing we came across was a sign telling us if we couldn’t make it down the first boulder crawl, not to bother with the rest of the trail. Needless to say, Jenny took it all in stride, and again more than compensated for my lack of having any idea what I was doing. We rumbled down the flight of rocks, coming to rest on a trail just a few inches wider than our Wrangler. For the next hour, Jenny took us back in time. We clambered up and down some gravity-defying inclines on our way to an enormous gaping sink hole exposing a few million years of sedimentary layering. On the way back we visited the Seven Sacred Pools, from where General Crook marshaled his campaign against the last of the Apache. Jenny never missed a step. From start to finish, all I had to do was point her in the direction we wanted to go, and our girl’s 285hp took care of the rest. Sadly, with our first two trails down, we were nearing the end of our four hour escapade. We turned back towards Barlow and, with heavy hearts, turned over the keys.

The first thing we came across was a sign telling us if we couldn’t make it down the first boulder crawl, not to bother with the rest of the trail. Needless to say, Jenny took it all in stride, and again more than compensated for my lack of having any idea what I was doing. We rumbled down the flight of rocks, coming to rest on a trail just a few inches wider than our Wrangler. For the next hour, Jenny took us back in time. We clambered up and down some gravity-defying inclines on our way to an enormous gaping sink hole exposing a few million years of sedimentary layering. On the way back we visited the Seven Sacred Pools, from where General Crook marshaled his campaign against the last of the Apache. Jenny never missed a step. From start to finish, all I had to do was point her in the direction we wanted to go, and our girl’s 285hp took care of the rest. Sadly, with our first two trails down, we were nearing the end of our four hour escapade. We turned back towards Barlow and, with heavy hearts, turned over the keys.

Needless to say, getting back into our rental car was rather disappointing. If it hadn’t been for the unbelievably good taco truck we found on the way back, I may actually have shed a tear to leave Jenny behind. The next day at our conference was even less exciting, but the last drops of adrenaline still had me feeling like Superman. I finally understood why people buy those burly, lifted, totally unnecessary vehicles – because they must turn even the most blasé commute into an experience.

On the flight home, I thought again of the rugged pioneers who trekked across a continent in rickety wagons with every one of their earthly possessions in tow. I imagine they’d be pretty annoyed to know how easily some guy from the East Coast can do it now but undoubtedly proud that they paved the way. I tried to look out the window to catch one more glimpse of the great cactus strewn expanse where roads are once again optional, but I was stuck in an aisle seat. I didn’t care. We’d had an unforgettable adventure. And, more importantly, I was in an exit row.

~Amir