January 22, 2018

Traveler’s Rule: International travel will always be marked by adventures with foreign showers and toilets. This morning has already held true. Delighted to even have hot water, I prepped for my first shower. Dr. Sudha warned us yesterday, “There may or may not be a shower curtain, so make sure you put some towels on the floor to catch the water.” No problem, I thought.

It took 3 full-sized towels to mop up the lake on the floor. If I were wise, I would have toweled myself off and then cleaned the floor. Air-dry it is.

I woke up at 4:30am Kigali time (9:30pm EST) and couldn’t fall back asleep. For a second, I was startled by the mosquito net I’d wrapped myself in just a few hours earlier. I can get pretty claustrophobic at times. This might be one of them.

Breakfast is served each morning at our hotel, buffet style. As I’m writing and waiting to meet the team, I can hear the staff singing as they prepare the morning meal. I’m counting down the minutes until 6:00am when I get to experience my first cup of Rwandan coffee.

Breakfast did not disappoint. I’ll be eating fresh fruit and coffee for the rest of the trip each morning.

We walked up the hill from our hotel to the University Central Hospital of Kigali (CHUK) to join the team for 7:00am rounds on the patients in the Emergency Department. Dr. Noah, the ED Attending, is a US-trained Emergency Physician who is here for 7 years helping Rwanda reestablish its healthcare system.

After the genocide in 1994, many of the country’s doctors were either killed or fled the country secondary to the violence. That left a huge deficit in trained personnel that the country has been working to fill ever since. Grants have allowed many US physicians to come here and train the residents in an effort to rebuild. Rwanda opened its second medical school a few years after the genocide and plans to open a third in the near future. They have made amazing strides in a short time.

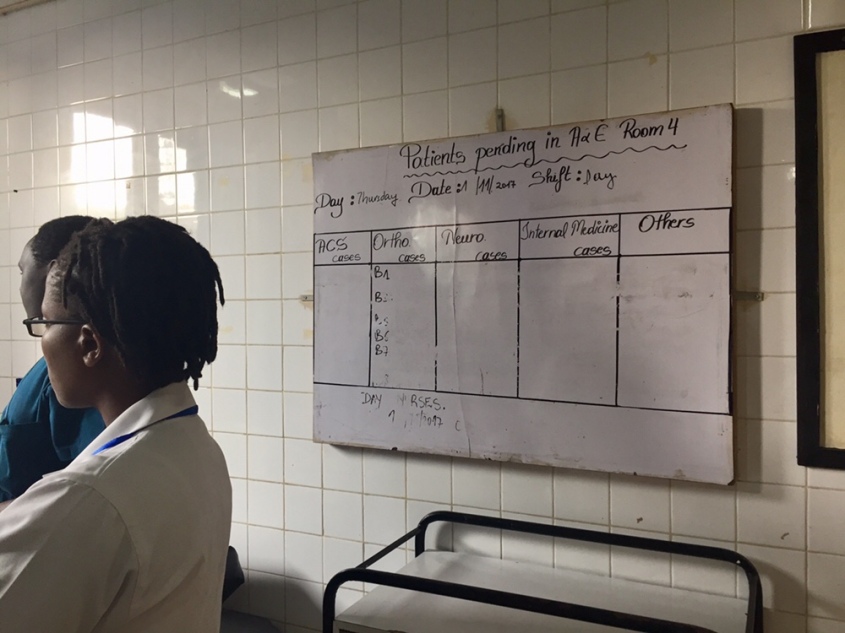

While I generally hate rounds (there’s a reason I chose Emergency Medicine), these were not your typical boring, Internal Medicine-type Rounds. The ED is organized into 4 large rooms, each with multiple beds with short curtains separating each.

The RED room is the resuscitation room for the sickest patients and contains 4 ventilators, one of which is currently out of service. I’m told the others are intermittently reliable. Resources are limited but they are providing excellent care with what they have. There we find multiple patients suffering from opportunistic infections, attributed to their HIV. There’s a YELLOW room with 6 beds. When RED patients improve, they are transitioned to this room. Here we found multiple patients suffering from trauma related mostly to the high rate of MVCs as I mentioned yesterday.

In bed 3, there’s a 38 year old man who was injured when a tree branch he was cutting fell on his neck, severing his spinal cord, resulting in quadriplegia. Rounds are conducted in English, but most of the patients we care for speak Kinyarwanda, Swahili or perhaps French. In a language I assume he doesn’t understand, we discuss his poor prognosis, as Rwanda has no long-term care facilities with spinal cord units, and motorized wheelchairs are a luxury available only to the super-wealthy.

He lays there on his back, with a cervical collar in place, staring at the ceiling and unable to make eye contact with us. We don’t speak to him, rather just about him, and I wonder if he understands his prognosis. I took a step forward, perhaps to make the interaction less cold, and realized he was crying. Although he’s stable right this moment, he’ll likely die in a week.

In room 3, the GREEN room, we meet a man who has suffered a femur fracture after a motorbike accident. He’s in the minority here as he has no insurance. Rwanda has a public insurance program where citizens pay minimal monthly fees, and if care is needed, the government pays 90% and the patient 10%. 5-10% of Rwandans choose not to participate, and unfortunately for this gentleman, he is in that minority. Unless in the case of true life threatening emergencies, labs and imaging are not ordered, medications withheld and surgeries postponed until the patients pay. Because of this, patients can spend days, weeks and in one case relayed to me, a month waiting to gather the required funds.

This man has no insurance and has no family or support system that could assist him with funding. He needs an orthopaedic surgery to install a metal plate to reattach the two ends of his femur. “Should we consider taking up a collection again?” offers Dr. Noah, and I realize this is a common challenge. We realize we aren’t going to solve this man’s problems quickly, and move on to the next bed to keep Rounds moving along.

After rounds we made our way just outside of the Emergency Department to Service d’aide médicale urgente (SAMU), the country’s ambulance service. Rwanda is 1/4 the landmass of Virginia, with a population nearly equivalent to that served by the Old Dominion EMS Alliance (ODEMSA), our regional EMS alliance for Central Virginia. SAMU staffs nurses and nurse anesthetists on the ambulance. Their training in prehospital medicine and trauma is minimal and variable, as there’s no standardized curriculum such as EMT and Paramedic. Most of the nurses and CRNAs worked in the ED prior to SAMU. The CRNAs can intubate and manage advanced medications, but the nurses cannot.

The ambulance bay contains a hodge-podge of ambulances – one way past its prime and slated for auction, another with random German writing which was donated, and another that could rival any newer model ambulance in the US. They utilize SUVs as smaller transport units, the backs of which look quite similar in setup to a medical helicopter. No CPR in these I’m afraid, but they look pretty darn cool and provide versatility in the crowded streets.

On the side of each ambulance is “Imbangukiragutabara,” meaning “Fast to Save.” We asked for help pronouncing it.

Because of their compact size, there’s really not room to ride along as an observer on the ambulance. I did however get to see the 912 (their 911) Dispatch Center that services the entire country. Calls come in from both landlines and cellular phones, but pinning down the exact location of the patient who needs care is challenging for many reasons:

- Most houses don’t have numbers. Most callers are members of a citizen brigade of non-medical personnel who live out in all the villages and volunteer their time to help with emergencies. Fortunately these volunteers know their neighborhoods inside and out, and can take SAMU to the patients.

- Cell phone calls don’t send the dispatcher any location data. In the US, we have federal regulations (Enhanced 911), mandating the data that cell phone carriers must provide to 911 centers. This doesn’t exist here.

- Cell phone calls frequently disconnect. In the US, if this happens, the dispatcher can redial the initial number that called. Rwanda 912 will also try to call back, but if no one picks up, there is nothing they can do after that. In the US we often do location welfare checks if calls disconnect, but without early transmission of location data, this option disappears.

I had more to add for the day, but the WiFi has slowed to a crawl, and I need some sleep before tomorrow. Our day is packed with plans to visit the Ministry of Health, prepare the equipment for our course, and see the Genocide Museum.

~Steph

Explore other days in Rwanda:

Rwanda Day 1 | Rwanda Day 3 | Rwanda Day 4 | Rwanda Day 5 | Rwanda Day 6 | Rwanda Day 7 | Rwanda Day 8 | Rwanda Day 9 | Rwanda Day 10/11

This was so good, honey. You’re doing a great job. Really interesting. Keep them coming! Love you, Mommy.

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

Very well done. Brings back memories of my “Operation Smile” experience. Written for both the medically trained and those who are not to understand. You have a gift.

LikeLike

Awaiting “ Rwanda Day 3 “ with bated breath !

LikeLike